When was the last time anybody saw us beating, let’s say, China in a trade deal? They kill us. I beat China all the time. All the time — D. Trump

I’d like to use this opportunity to talk about China . . . and recycling.

The preoccupation with China, and specifically trade with China, in the election has reminded me about one of my favorite Materials Stories: The Minjinyu 5179 Incident. If you’ve heard this one, skip down to here.

I had just moved to Doha in the Fall of 2010, and was charged with fashioning the syllabus for DESI510: Materials and Methods, a new course for the MFA program. Trying to set the stage for “the importance of materials knowledge in not only a design career, but any career”, I was mining the news for current events that would highlight – ideally in some scandalous context – this very notion.

Little did I know what the world had in store for me.

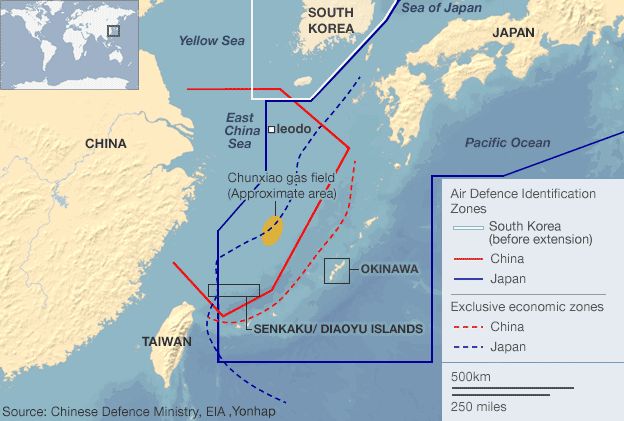

In September of that year a Chinese trawler, the aforementioned Minjinyu 5179, was sailing in the waters off the Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands, one of many (very many) disputed groups of islands in the Pacific. The trawler, deemed to be fishing in Japanese waters, was approached by Japanese Coast Guard vessels and ordered to heave to (maritime speak for “stop”): it chose, instead, to ram the Japanese vessel and make a futile run for it.

Scandal, ahoy! (And, no, it’s not about the fish.)

Senkaku is the uninhabited islands’ Japanese name, and Diaoyutai is their Chinese name, and they weren’t much more than “turn when you see them” navigational signals for a long time. While the Japanese claim to have “discovered” them in 1884, the Chinese show written records of them dating back to 1403 – though they don’t necessarily say that they wanted them. Then.

In 1895, who found them first kind of went out the window as Japan formally annexed the islands as part of their spoils from the First Sino-Japanese War. A few wars later, in 1945, when Japan surrendered to the United States at the end of World War II, they fell under US occupation but were later returned to Japanese control, with the passage of the Okinawa Reversion Treaty by the US Senate, in 1972. Coincidentally, in that same year, China also claimed ownership of the islands. Curious.

While the islands were mere road signs in 1945, in 1969 they had a Beverly Hillbillies moment when a UN commission identified possible oil and gas deposits in their vicinity, and they were suddenly much more valuable than their previous use as a bonito-processing station. While this was perhaps the origin of China’s renewed interest in the islands, it was far from the end; and the current ownership map looks like this:

So, you’ve got two countries locked in a dispute about territorial ownership, a bunch of boats stepping on each other’s proverbial toes – a diplomatic bruhahah was bound to arise. And it did.

What made this particular dispute SO interesting to me – beyond a bunch of bumper boats in the East China Sea – was how China reacted: they blocked shipments of rare earth elements to Japan.

Rare earth elements, or rare earth metals, are things like cerium (Ce), dysprosium (Dy), europium (Eu), gadolinium (Gd), holmium (Ho), neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), promethium (Pm), samarium (Sm), terbium (Tb), thulium (Tm), and ytterbium (Yb). Apologies if I have edited out your favorite.

While most of us have never heard of dysprosium – much less how to pronounce it – it and its rare siblings are the bedrock of the technology sector. So much so that the Japanese refer to rare earth metals as the “Seeds of Technology”. (Well, that’s what these people say. I wish they were Japanese . . . )

OK, these things are important, and China doesn’t want Japan to have them – so?

At that time, China produced – depending on who you asked – anywhere from 90-99% of all of the known rare earth metals, so if they wouldn’t sell to Japan, it would effectively stop their ability to produce technological products – which one could argue accounted for almost a quarter of the country’s GDP. Game – potentially – over.

Suddenly, stuff like this “dirt” was bringing a country to its knees.

This was DESI510 gold – GOLD!

The Chinese were using materials – esoteric ones at that – to threaten the Japanese with economic ruin. In the end, at least according to my syllabus, the Japanese relented, apologized to the Chinese, and restored the sustaining flow of these raw materials to their industry.

In reality, it appeared that the withholding of materials was a ruse, the Japanese released the captain of the fishing vessel only after the Chinese held their feet to the fire diplomatically, and both they and the Chinese escalated their rhetoric about sovereign domains. World War III was predicted, and rare earth metals were forgotten.

Until a couple weeks ago.

A recent Wall Street Journal article, entitled “China’s Rare Earth Bust”, led with the telling of Honda’s recent development of a hybrid engine that didn’t use any rare earth metals – a pretty prodigious feat. It took this achievement as proof of one of Julian Simon’s “theories” – that “human ingenuity” has the capacity to overcome shortages in natural resources.

I had never heard about Simon, but the concept that high prices or shortages of materials leads to greater innovation is not a new one. We mostly talk about it in terms of energy prices: the higher the price of traditional sources like oil and coal, the more attractive renewable forms of energy – like wind or solar. The point there is that “clean” (but more expensive) technologies benefit – that’s good.

The Journal also made the link to energy but, instead, chose to highlight fracking – fracking – rather than clean energy. This is what fracking looks like when oil prices go back down.

It went on to say that higher rare earth prices led to – surprise – more efforts to mine them, as the returns were better. This is what more mining looks like – in this particular case, in China.

There was one line about recycling: “Metals firms began recycling more lanthanum, dysprosium and other coveted elements from industrial waste.” One line. This would have pleased Mr. Simon, who also famously wrote the following:

“Because we can expect future generations to be richer than we are, no matter what we do about resources, asking us to refrain from using resources now so that future generations can have them later is like asking the poor to make gifts to the rich.” (buy the book here!)

Without belaboring the idiocy of the Journal’s angle in this article, it is the perfect place to return to my original point – recycling – and a question that has been in the air for a long, long time:

Why in the world hasn’t Apple, or any other tech producer, changed their model from a sales-based to a leasing-based one?

We have all (mostly) agreed to bow down to Moore’s Law and consume products like phones and computers at a voracious pace. Just this week, Apple announced that it has sold – drum roll, please – One Billion iPhones.

In my class, I used the following statistics: every one million cellphones recycled would yield 750 pounds of silver, 50 pounds of palladium, 70 pounds of gold, and 35,000 pounds of copper. Using only iPhones, one can simply multiply by one thousand to get the impact – and the value of materials at stake here. In today’s market, 70,000 pounds of gold is worth US$1,373,500,100. Give or take. And, remember, this is just iPhones – according to this site, there is approximately $9.00 worth of gold in every computer.

As my wife is painfully aware, I am a bit of a freak and save all of my old technology. I don’t know, I guess I harbor the fantasy that sometime in the future, the only thing that is going to save us is a TRS-80. Or a 512k Mac. Or a Motorola Star-Tac. Or a Visor Edge (which looks surprisingly like an iPhone). I could go on, but you get the picture.

It was not lost on me, however, that the real value of all of these objects drifts to virtually nothing two years after they roll off the line. We really do feel like they are simply worthless.

In my list of trash antiques above, however, is an omission: the first computer I actually “worked” on, the Original 128k Mac. Why don’t I have that one? The reason is simple: when I graduated, there was an offer to trade in the 128k model for a discount on the new, 512k model; and when the price of a computer – in 1988 – was almost $3,000 (more than $6,000 in today’s dollars), you would take any discount you were offered.

In addition, early PCs – and even early laptops – were modular and upgradeable. My beloved G3 laptop (not purchased because it was codenamed “Lombard”, but it was an added bonus) had an easily removed keyboard so that the user could add RAM or change the processor. Now, we get beautifully honed – but very closed – aluminum cases that allow for no changes to hardware, and fewer and fewer ports to boot.

No ability to upgrade means no future value means the trash heap. Wouldn’t it make more sense to get all of that equipment – and all of the included materials – back? We trade in our cars, why not our technology?

The benefits of leasing equipment would be many. As a materials person, the obvious benefit is control of materials: if you own the phone, you own the materials in it. Play your cards right, and you could reduce your purchases of virgin materials to almost zero. This would also encourage the design of more modular products, ones that would be easy to disassemble and “mine” for parts and materials.

Google, building on Phonebloks, is already venturing in this direction with the Ara. In addition to creating a modular, upgradeable, waste-reducing phone, they are also creating a community. This is a key part of any/all retail strategies.

When I buy a phone – straight up – I own it. When I lease a phone from a wireless carrier, I have a relationship to that carrier NOT the manufacturer of the phone. Additionally, I will most likely want a divorce in a very short period of time (yes, I mean you Verizon).

If I leased a phone from a manufacturer, I would have an ongoing relationship with them, and would be a known customer (remember, it’s cheaper to keep customers than get new ones) and a captive source of information for them. I would no longer hesitate about purchasing an xPhone 24 for fear that the xPhone 25 will be released next month, damning my piddly 24 to immediate obsolescence.

The manufacturer, on the other hand, doesn’t worry about abdicators – unless they turn a deaf ear. They would have a constant line of quantifiable metrics from their community, and could tell which features to keep and which to abandon based on users keeping or returning their equipment.

I am not insinuating that Apple doesn’t make every effort to get this sort of information already, but the change in model would make the whole process much more seamlessly integrated. Information, materials, and customers would flow in a much more closed loop.

I’m not a big fan of Google – ’cause I’m reading this – and I find it interesting that in this case, a hardware scenario rather than a server scenario, I think that they are very much on the right track.

Control your materials: it can be a benefit to you and your customers.