As Giving Tuesday has just passed (which, as a recent expat, I had never heard of), I thought that I would reflect on what I see as a troubling phenomenon: taking, everyday, as if there’s no tomorrow.

Having lectured on the topic of Sustainability for a number of years, the standard assumption from most people is that the concept is solely based in some form of environmentalism. As a “materials” person, I can certainly appreciate that this is a large part of the concept; but I do subscribe to the idea that Sustainability is anchored in three specific areas. The environment is one, but Sustainability also includes human capital and economic capital.

Possessing a different middle consonant in my master’s degree – a “B” instead of an “F” – than most of my colleagues, that last leg of the triad has also always been of interest to me, and it is the least spoken of among the three. Yes, Triple Bottom Line and the Three Ps do reference it, and that consonant refers to the most unsustainable element in the economic review: Profits.

Without belaboring the point (too much), “Normal Profit” is defined as a company’s state when total costs (including opportunity cost) are exactly equal to total revenue. Or, put another way, “Normal profit is defined as the minimum reward that is just sufficient to keep the entrepreneur supplying their enterprise.” If a company makes more than this base level, it is referred to as “Super Normal” and “Abnormal” and – interestingly – “Accounting” profit.

We hear plenty about profits that seem “abnormal” these days, but those profits are hardly undeserving of the moniker:

“US banks just recorded their most profitable quarter EVER”

“Apple’s iPhone Has Set a New Profit Record”

US banks took home profits – profits, not revenues – of more than $43 billion in one quarter. In the case of Apple, their share of the smartphone market profit was 104% (is it a “share” if it is more than 100%?), which translated to $8.5 billion. For one product line, from one company, in three months.

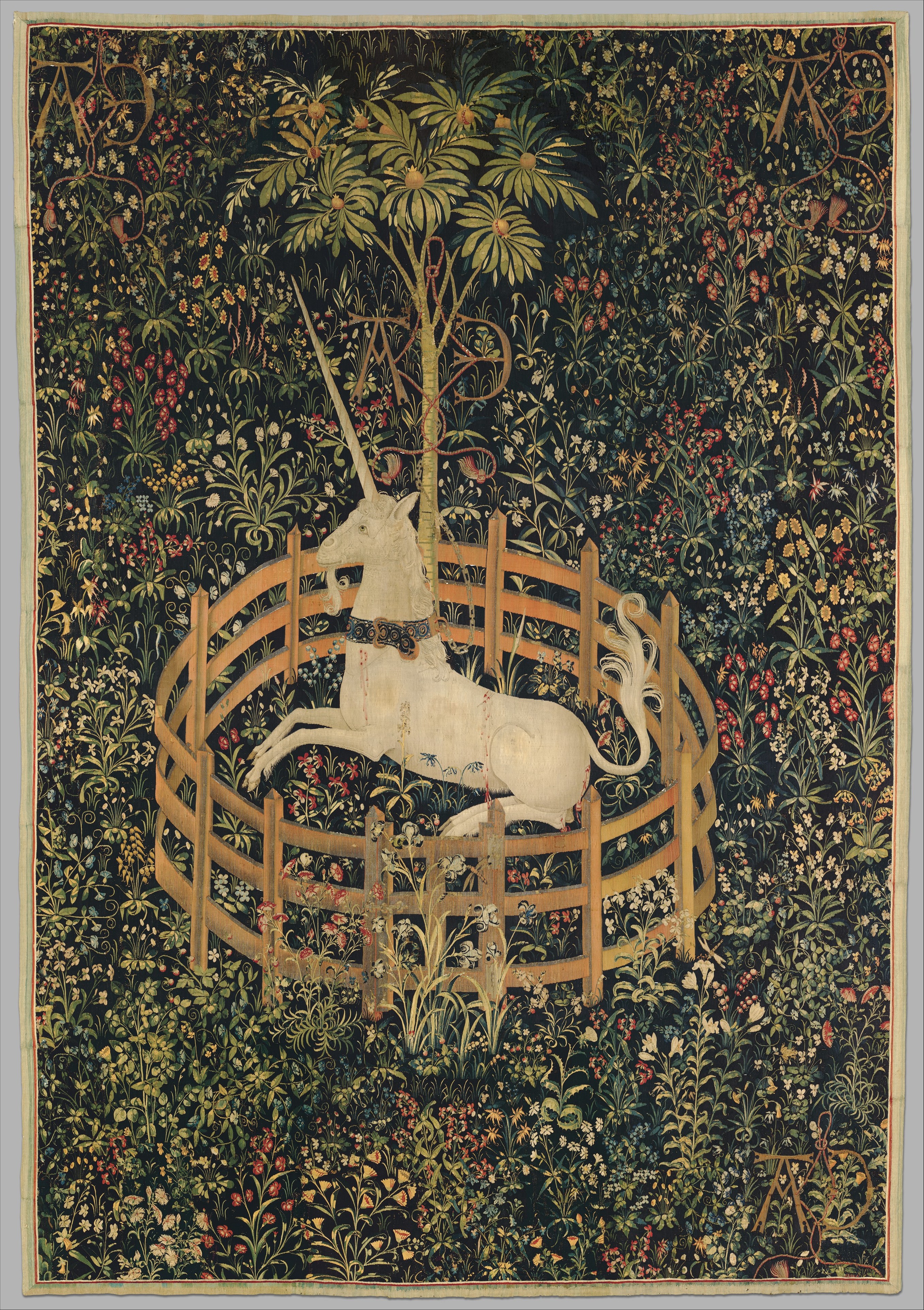

Anyone who has even the slightest interest in “raising capital” no longer thinks of a unicorn as a mythical, horned horse: no, a “unicorn” is a startup (which is a loose definition in and of itself) with a market capitalization of more than $1 billion. Many people are also familiar with the investment term “tenbagger”, which refers to an investment that appreciates to ten times its initial price – meaning a 900% increase.

I would argue that these are unsustainable concepts, and that the world of finance has radically altered global economic sustainability through its pursuit of truly super-normal profits. This impact has also had profound effects on the way Academia both educates its students and conducts its research.

The focus of many educational programs – from design to business – is on “disruption” and “innovation”: two words that (if it were up to me) should be relegated to that particular Hell that now contains “granular”, “synergy”, and “robust”.

Why is the focus on these elements? Because that is what investors not only want, but need, to see in a business. And the investors are driving the school bus.

I’m just worried about where it’s headed.

One of the most high-profile examples of where I do see it headed is/was Theranos. The moment that Elizabeth Holmes dropped out of Stanford and used the money that her parents had saved for her tuition to start the company, the diversion of money from Academia to Industry had begun. Ultimately, Holmes and company would raise more than $700 million from investors, and would have a market capitalization of some $9 billion earlier this year. Then, the gravy train (sorry, mixing my transportation metaphors) went off the rails.

Turned out that the magical Edison (did they have to license that name – and is he rolling in his grave?) technology, shrouded in “proprietary” secrecy, wasn’t so magical after all. Thirteen years of research, and hundreds of millions of dollars, were spent in support of what appears to many as a complete fraud. While Theranos is the most spectacular implosion, there are many other research-based startups (technology mainly, but also other medical ones) that are operating on the fringes of what is possible.

[For more on this, I recommend Paul Reynolds’s blog . . .]

Which brings me back to my world – the Material World.

In that world, one of the most dynamic – if not THE most dynamic – areas of research and exploration is Synthetic Biology: effectively, designing organisms that can either produce novel compounds or produce known compounds through significantly more efficient and sustainable methods.

Research into this area is the very definition of innovative and disruptive. Metabolix and Danimer Scientific have been working to expand the market for the biopolymers known as polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). PHA is a plastic produced by bacterial fermentation using basic, natural foodstocks like sugars (corn syrup) or oils (canola oil). Modern Meadow is working with bio-engineered collagen to produce synthetic leather that is virtually identical to the real thing (and, it would seem, is also the stepping stone to other materials).

All of this work will be made more efficient, economical, and “tunable” with a thing called CRISPR.

One of the most dramatic breakthroughs – period, full stop – in recent years is the identification, and exploitation, of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, aka CRISPR. These repeating sequences of DNA are believed to be a sort of “genetic memory” of past viral invasions; but their importance is in their use as a guide for the precise “editing” of DNA. With a tool like this, highly targeted organisms can be efficiently created for the production of an ever-widening range of materials. However, to focus on materials is to miss the real point of the technology: using this tool, the cure for a wide range of genetic disorders appears well within reach.

The full genetic modification technology is known as CRISPR/Cas9 and, according to James Haber, a molecular biologist at Brandeis University, “[it] effectively democratized the technology so that everyone is using it. It’s a huge revolution.” Previous technologies were both expensive and complex, but the new technology can be accessed for as little as US$30. This is not to say that anyone with enough money for a Star Wars action figure can start churning out glowing rabbits: the technology is only “democratized” for knowledgable researchers.

Or is it?

A massive legal battle is currently underway to determine who gets to lay claim to the ownership of the technology; and the combatants are – remarkably – not companies, but schools. However, where there is smoke, there is fire – and the primary reason (not the only reason) for the battle is how much money is at stake.

On team Left Coast is the University of California, Berkeley (and the University of Vienna, but they always come after the comma, so I’m putting them as “teammate”), and on team Right Coast is the Broad Institute, a partnership including Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology: no slouches are to be found at the table. The parties have been engaged in some form of patent litigation since the beginning of 2014, and early last year UC Berkeley filed a “patent interference” motion that effectively sets the stage for a “winner takes all” outcome.

Exciting as that is, the real story is what lies behind the tables. Money, and lots of it.

In the three years since the technology was discovered, more than $600 million has been raised (other estimates put the number at more than $1 billion) by a number of companies hoping to exploit the opportunity.

One of those companies is Editas – get it? “edit”? – Medicine, whose founders included (note the past tense) a member from each of the teams that submitted patent applications. Editas have already licensed the technology from the Broad Institute (Team Right) and, based on this arrangement, raised some $200 million in venture funding and then, just this past February, went public – raising an additional $95 million. Not long after that, they saw their market capitalization eclipse the mythical $1 billion mark.

And they don’t even know if they own the technology.

It is numbers like those that will keep this case in court – money, and the absolutely bizarre circumstances of the patent filings. (In a nutshell, both teams filed for a patent, but in between the two filings, the law changed from “first to invent” to “first to file”. Berkeley was the first to submit their claim into the system in 2012, but the law changed in March of 2013 to recognize “first to file” – and when Broad filed later that year, they requested an expedited ruling and effectively leapfrogged the Berkeley submission that was waiting in line per the earlier rules. ( I was going to suggest a moneyed conspiracy theory, but the Congressional Act that created the changes was introduced in early 2011, and spinning that level of web is beyond me . . .))

At the beginning of the research process, the two programs were collegial: in January of 2013 the lead researcher for the Broad wrote to the lead researcher at UC Berkeley, “I met you briefly during my graduate school interview at Berkeley back in 2004 and have been inspired by your work since then.” He continued, “I am sure that we have a lot of synergy and perhaps there are things that would be good collaborate on in the future!” As mentioned previously, the two would also sit together on the board of Editas. Then, rather than share – as universities often do – the lawsuits began.

At the core of the current debate is whether the work that UC Berkeley did was informative enough to cover the work that the Broad did, or, in a great bit of plain-speak, “I’ve given you the recipe for a Western omelet; how good a chef do you have to be to use that to make a soufflé?” Berkeley claims that anyone in the field could make the leap, Broad says only a genius – their genius – could.

What is at stake is more than the future of a business sector that is predicted to grow to be worth some $3.5 billion in revenues in just two years. As a point of comparison, the in vitro fertilization industry took almost 35 years to become a $9+ billion industry. What is at stake is the future of truly “democratic” research that has a tremendous positive impact on the public good.

Research is a process, and a slow one usually. Additionally, to paraphrase another researcher – Isaac Newton – people see farther by standing on the shoulders of those who went before them. Giants or others. Research done in schools and public institutions is validated by peer-review, not investor contributions, and is made very public. (Whether anyone outside of their circles can understand what is being said is another story completely.) Unfortunately, in a world that is rapidly running out of opportunities for Tenbaggers, this kind of research is being commercialized at an alarming rate, and for the financial benefit of very few.

Schools are in the business of creating productive people, as well as contributing to the global body of knowledge. As businesses, they also need to earn “normal profits”. In the truest sense of the word: I know that there are a wide variety of structures for educational institutions, but for the vast majority – the nonprofits – it would seem to me that they need to earn the minimum reward that is sufficient to keep the institution supplying their clients.

Licensing technology is a tremendous source of revenue for many schools, and many need that revenue to earn those normal profits; but many don’t. The total value of the top ten university endowments is $170 billion. Ten schools, and – yes – Harvard and MIT, the two partners in the Broad Institute are on that list at number one and number five, with endowments of $37 and $13 billion respectively.

Research and development cost money, and no one could argue that they aren’t the core of all great universities. These institutions are ongoing concerns, and they need to cover costs – including those that give them a competitive advantage in the future. By the same token, for-profit businesses should also be able to make more than “normal” profits – but how much more?

Until we – as a global society – come to terms with what we consider an acceptable level of profit, we are going to continue to see wealth aggregate into the hands of the few. That aggregation is currently at its highest concentration in modern history: as of this year, 62 people held the same amount of money, some $1.76 trillion dollars, as the bottom half of the world’s population.

Beyond these few individuals are a similarly small group of investment firms that control equally vast sums of money. Blackstone, Vanguard and three other funds control more than $14 trillion – and entire sectors of the global economy. They, too, are radically impacting the world of research and development on a corporate level.

These investors, both individual and corporate, cannot continue to seek ever-growing levels of profit without seriously harmful impacts on the global economy – and global welfare. Furthermore, if investors are allowed to infiltrate Academic Research, the answers that the world needs – to heal the sick, to feed the hungry, to heal itself from the ravages of humanity and survive the next hundred years – will literally be sold to the highest bidder.

So, back to where we started: Sustainability.

We have limits on the amount of fish that can be pulled from the sea, because without some fish now there won’t be any in the future. When a company cuts a tree down (with or without someone around to hear it), they plant two in its place to ensure a future supply.

There are no such laws in place on Finance – and it is wholly unsustainable. We cannot let this destructive quest for More invade the halls of Academia.

(and don’t even get me started on Scott Pruitt . . .)