My love of socks notwithstanding, the Fashion Thing – in general – is my least familiar territory. I love to see Design as a solution to a problem, and I can’t really see how claiming “_______ is the new black” does that. I absolutely believe in the power of personal expression and individuality, but I feel that Art does that better – so, maybe, Fashion is more like Art than Design for me?

“Tech” is another aspect of the larger Design Universe that I am uncomfortable with. However, schools around the world promote Arduino in the classrooms and technology companies in their incubators, so – whether I like it or not, there is no question that Tech is here to stay.

I do, however, “get it” as far as Tech is concerned: it has the greatest universe of possible applications, and the best margins in the business world. The question I always come back to, though, is “how many apps can the world really need?” (And, you’ve heard it before, don’t get me started on Uber . . .)

That said, I am a firm believer that all of us – from designers to materials scientists to coders – will be coming together in service to a trend that will redefine the way we live: wearable technology. It is my belief that Wearables represent the best of what Fashion and Tech can offer.

As with most of my research, I wanted to see where it all began: what was “The First Piece of Truly Wearable Technology As I Have Chosen To Define It”?

[I am not talking about eyeglasses or wristwatches, nor am I referring to Walkmen or GoPros. I am talking about garments that integrate – through more than duct tape or a couple of straps – some form of technology for the benefit of either the wearer or those around them.]

Thinking about my parameters, I assumed that it would have occurred in one of the various space programs – either US or Soviet – of the late 50s/early 60s.

As with most of my assumptions, this one was completely wrong.

The early “space suits” were glorified plastic bags that only served to maintain pressure (and a breathable environment) for the wearer.

Developments were focused more on increasing mobility – from pretty much none – than adding technology. There were the obvious communications additions but, as mentioned earlier, I am not interested in projects where they simply bolted a microphone to a helmet and put a radio in a backpack.

Digging around, past the super-appealing but most likely “fake news” Electric Girl Lighting Company, past the groundbreaking 1950s artworks of the Japanese artist Atsuko Tanaka . . .

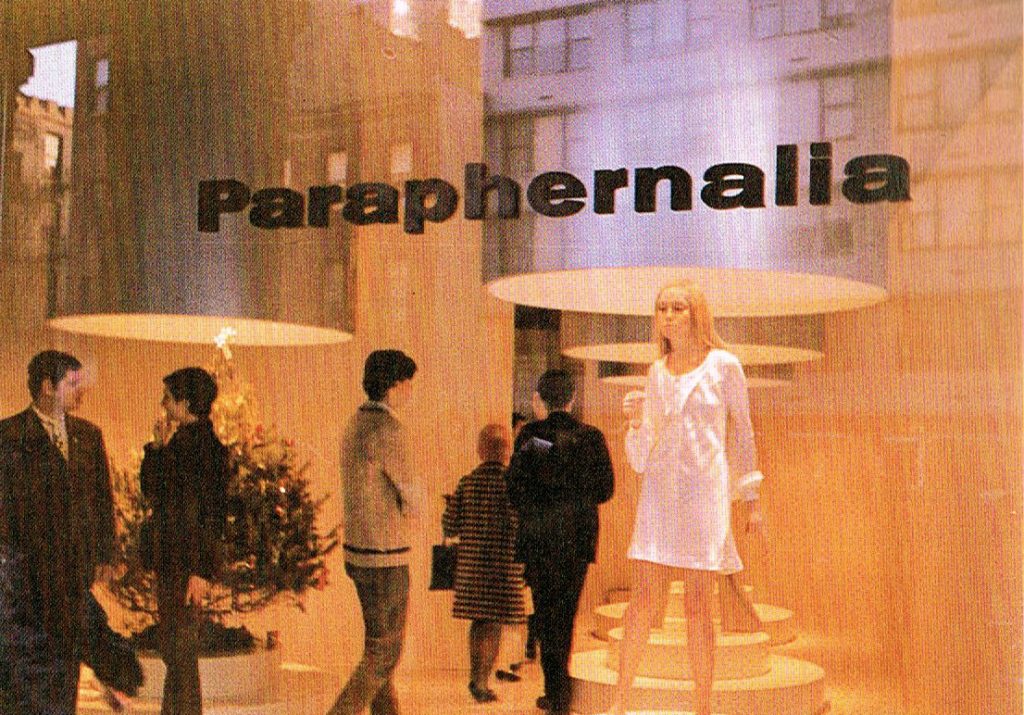

and venturing deep into the history of technology/fashion/ design, brought me to an unusual place: Madison Avenue, shopping mecca of New York, and a generally mind-numbingly boring corner of the world (see my opening comments on Fashion).

There, in the mid 1960s, a boutique called Paraphernalia invaded the shores of the otherwise staid Upper East Side like a pirate ship at a Yacht Club Regatta.

The store, a transplant of London’s Mod obsession, featured outfits that were not dry-cleaned but rather wiped down with a damp cloth. It was frequented by Edie Sedgwick, and it featured Betsey Johnson as a member of the creative team (she had been an assistant in the art department at Mademoiselle – the Teen Vogue of its day – after winning a contest to be a guest editor). The store also hired some of the most outrageous talent in the fashion industry: one of whom was a young woman (though they were ALL young women in the design department) named Diana Dew.

Mind you, I had never heard of the store – much less Diana Dew – when I wandered into this rabbit hole, so to hear that Johnson was there, that Sedgwick was their Number One Fan (and brought Andy Warhol along), that the Velvet flipping Underground played the opening party, it all pretty much blew my mind. Man.

That this intersection of Design, Music, and Youth gave birth to some remarkable things was not so hard to wrap my head around. What was hard to fathom was that a.) so much of it was unknown to me and to others interested in this area, and b.) many of these groundbreaking designers simply faded away.

The store was created specifically for young people: it was supposed to offer them the newest of the new at a price that they could afford. They hired young, mostly unknown designers and gave them free reign to create whatever they wanted to. They tapped into the psychedelic scene – with its music and focus on expanding minds through both pharmacology and technology.

Weird things were bound to appear – and where that happens, epiphanies happen. (Sadly, among other prescient aspects of the store, it heralded the arrival of “Fast Fashion” and garments that were envisioned as being worn only once before being disposed of.)

Given the anecdotal evidence – really all that is out there – it is shocking that Diana Dew is not better known in . . . some circle. She has very little written about her, despite stories of incredible accomplishment.

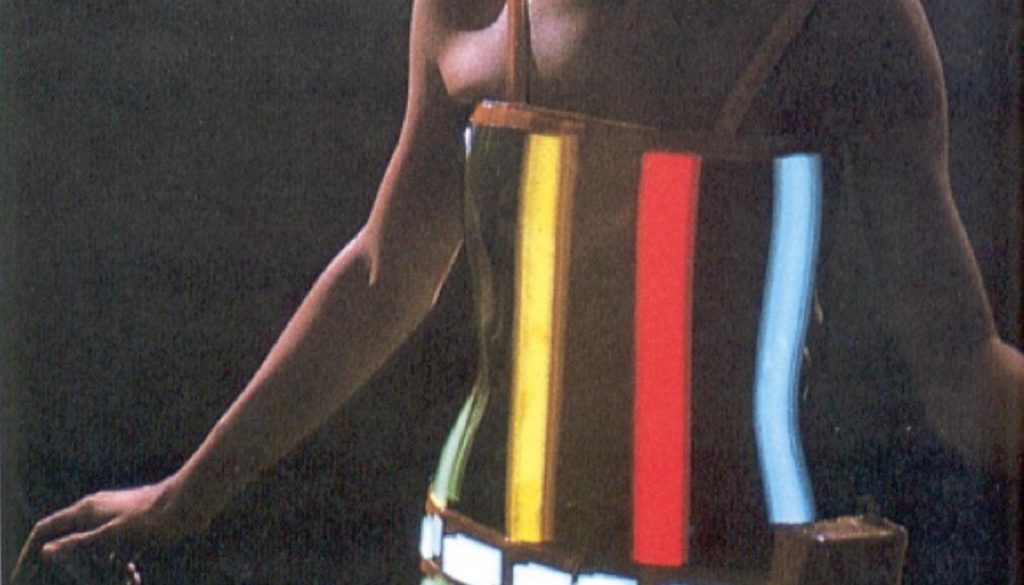

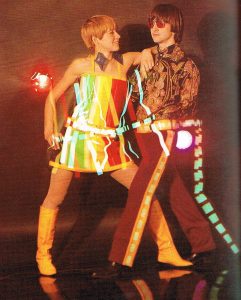

She worked with Bausch and Lomb to create specific tints for lenses, worked with Sylvania to create flexible electroluminescent (EL) sheets, experimented with thermochromatic (changes in temperature change the color of the material) pigments/materials, and she managed to devise a battery system to power her dresses (for 5 hours) that was small enough to wear on the belt of the dress – and was rechargeable (and I only read about a single mishap). Groundbreaking stuff.

(Again, for emphasis: we’re talking about 1965. EL wire and tape still astound people today . . .)

Like many of her creations, the dress was – as far as Fashion was concerned – pretty basic: a par-for-the-course minidress with spaghetti straps, and without the inclusion of the systems she devised it would hardly earn a second glance. That might have been purposeful, as a sort of decoy to increase the surprise when the lights came on.

The various EL panels were connected to some combination of programmed circuitry and a potentiometer – basically a speed control that allowed the wearer to change the timing of the strobing of the lights. Step on to the dance floor, flip the switch, and the panels would light in a pre-programmed sequence – all that was left was to adjust the speed of the flashes to the music, and you were instantly transformed.

So, Diana Dew is hereby crowned the Mother of Wearables (in my book), and I look forward to finding out more about her; however, this has also been the mother of all diversions.

The investigation continues . . .